2022-07-22 - Blackberries

A summer tradition.

IC Date: 2022-07-22

OOC Date: 07/22/2021

Location: Taholah

Related Scenes: None

Plot: None

Scene Number: 7

"The blackberries are ripe."

Ada drops the remark into a casual phone call, and on her end, Jules immediately perks up. "Ooh. I'm off on Monday. I could come up then."

"Wonderful. I'll see you Monday morning, then."

It's been a yearly tradition for as long as Jules can remember. When she was little, Ada taught her patience by watching the progression of the berries, from the white airy flowers to hard green spheres that gradually reddened over the course of the summer. Jules always wanted to start picking them too soon. "Be patient," Ada would say when the little girl's face would screw up at the sourness. "You have to wait until they're black. Wait until they're not so hard, when they plump up. Just wait."

In earlier years, Alex would come too. The age difference was such that Jules, from her lofty vantage point of nine, would grow exasperated with her much littler brother. "You're smooshing them! Alex! Ugh! STOP!" The five year old would just giggle and deliberately squash his chubby hand into the bowl of berries, turning it into an inedible mess and staining his hands purple and, inevitably, his shirt too. "GRANDMA! Alex messed it all up!"

"Be patient, Jules," Ada would instruct again, unable to hide her smile as she'd stoop to collect her giggling grandson. "Alex is just doing it to wind you up." Harder giggles. "It's okay. We can pick more."

Alex lost interest around the time Jules was a teenager, more inclined to play soccer in the street with his friends. It turned into a summer routine for just the two of them. Jules slammed the Pyrex dish into the sink so hard she nearly broke it the first time her cobbler didn't set, berries too watery and biscuit topping raw in the middle. "Jules!" A sharper note from Ada, now. She's old enough to know better. "Honey." Softer, this time. "Be patient. This is how you learn." Jules, still frustrated, had the presence to look guilty at her outburst. "Just leave it for now. We'll go pick more and have them over ice cream."

Jules drives up early, arriving at her grandparents' humble home around mid-morning. Ada's waiting in the kitchen, containers stacked on the table for the harvest. She's slower now, though, wanting to finish her milky coffee first, then forgetting her wide-brimmed hat and wanting to go back for it before they've left the drive. Jules isn't used to her grandmother as anything but brisk, and the subtle changes strike her after nearly a year away from daily interaction. She's patient with her grandmother, but makes note, wondering.

It's a nice stroll to the nearest patch, where the briars encroach year by year on the roadway. Every few years, they have to be dramatically cut back. As promised, the vines are full of the season's first fruits, ripe berries among those slower to mature. Ada and Jules have both dressed for battle in their long-sleeved shirts, jeans, and close-toed shoes. They'll still come away with scratches on their hands or where the thorns snag in their sleeves, but such is the nature of it. "Start here, work our way to the right?" Ada suggests, and Jules agrees. They wade in.

Both women are silent at first, concentrating on their task and happy in each other's company. Conversation comes slowly. Not for the first time, Ada expresses how much they all enjoyed having dinner at Jules' house in Gray Harbor with all her friends. Inevitably, she asks after Mikaere (Charlie liked getting to know him a little better; her friends seem to like him, too). Jules' response spools out slowly as she picks. How he's gone back to New Zealand for a visit. How it involves a traditional ceremony. How he sensed it was time. Jules struggles to explain, here, perhaps because it's not her own culture and the reference points are different.

Not for the first time, Ada listens for the things that Jules isn't saying. This is how it's always been, even having extracted a promise a year ago, when all this began, that Jules would talk to her instead of bottling it all up.

"I think we're all getting stronger," Jules notes as she crouches to tackle a lower-level set of vines. Ada sticks to an easier range, these days. "Something about living in Gray Harbor. We're always being tested. We use it more and learn from each other. Do you think it's like a muscle, one that gets better with exercise?"

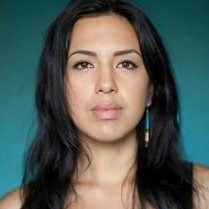

"Maybe," Ada says thoughtfully, glancing down. Jules' expression is hidden from her, and all she can see is the crown of her head, her long black hair efficiently pulled back in a braid. "I didn't find that it was like that for me -- but the worlds aren't so close, here. That might have something to do with it."

A longer silence.

"How come mom turned out so strong, then?"

Ada has never fully been able to explain it. Not to herself. Not to her husband, who was sick with worry when the seizures started and wanted his daughter to have the best medical care at Seattle Children's Hospital. Not to Sylvia's teachers, or the school counselors, or the child psychologist she agreed to let Sylvia see. Maybe, Ada reasoned at the time, the psychologist would give her daughter tools to cope with what she was experiencing, even if she never believed that the illusions were real, that the paranoia was justified. Ada looked in vain for psychologists and doctors that had that telltale glow, but Seattle was so big and so far away. It was like looking for a needle in a haystack.

"I don't know," is all she can tell Jules now in all honesty. "I don't know, honey."

Charlie didn't fully agree with Ada when she said she wanted to consult tribal elders and seek advice from closer sources. He'd do anything for his daughter, though, and anything for his wife. In time, he became a believer in the things he couldn't see. For a time, he turned to the Christian faith, wondering if his daughter was possessed and if faith might provide a resolution. Modern medicine couldn't explain it, and he hated to see his little girl drugged to a stupor. That wasn't a solution. Christian prayer didn't solve it, either. So why not turn to older ways of understanding? No one quite knew what to do with this precocious child, though, with powers of the mind beyond what they themselves could grasp. "We'll try to train her," they said, but how do you train a child who can do things you yourself cannot, and who doesn't have the control not to, nor to understand how only prevention will stop the seizures and the comas, will preserve her singular sense of identity?

"I can't imagine," Jules says eventually, "what that must have been like for you and Grandpa."

Ada can only smile a little, sadly, and reach down to stroke her granddaughter's head. "It's been a joy to raise you and your brother."

Jules leans into her hand for just a moment. Then she straightens, ready to move down to the next blackberry patch.

Ada doesn't inquire further into her granddaughter's life this afternoon. Patience.

Tags: